With the Affordable Care Act’s enhanced premium tax credits set to expire at the end of 2025, the Senate voted this week on competing approaches and failed to advance either. The Democratic-backed proposal sought a three-year extension of the enhanced credits; a Republican-backed alternative associated with Senate health committee chair Bill Cassidy emphasized government contributions to health savings accounts (HSAs) and a shift toward lower-premium, higher-deductible coverage. The votes left the “subsidy cliff” in place during open enrollment, heightening the chance that many marketplace households will face higher net premiums in 2026 unless Congress acts.

The dispute is partly about mechanics and partly about what “affordability” means. One camp frames the problem as monthly premiums and points to the credits as the most direct way to keep coverage within reach. The other emphasizes deductibles and out-of-pocket exposure, arguing that cheaper premiums can still leave families underinsured when they actually need care. On CBS's Face the Nation, Cassidy argued that “there has to be a meeting of the minds between Democrats and Republicans,” framing a compromise as one that addresses both premium costs and deductibles rather than picking only one.

Public messaging around the cliff has become a magnet for overgeneralization. Some commentary claims that the expiration will cause premium increases “across the board,” while other arguments minimize the impact by asserting that most people above a certain income threshold already have employer-sponsored coverage and therefore won’t be affected. Both claims point to real patterns—many enrollees do receive substantial help, and many middle-income workers do have employer plans—but neither pattern is universal. Marketplace enrollment includes self-employed workers, people between jobs, and workers whose employers do not offer affordable options at a wide range of incomes.

The policy fight has also triggered competing economic narratives. Supporters of HSAs argue they can reduce total household burden by giving people more control and pushing them into cheaper plans; critics argue that HSAs often shift risk toward patients by increasing deductibles and leaving sicker enrollees exposed. Separately, a more cynical narrative claims lawmakers are primarily protecting insurer profits by keeping the subsidy structure intact, while a viral legal claim conflates the subsidy deadline with the ACA’s constitutionality, suggesting the law is “illegal” and must be struck down by courts because Congress did not extend the credits.

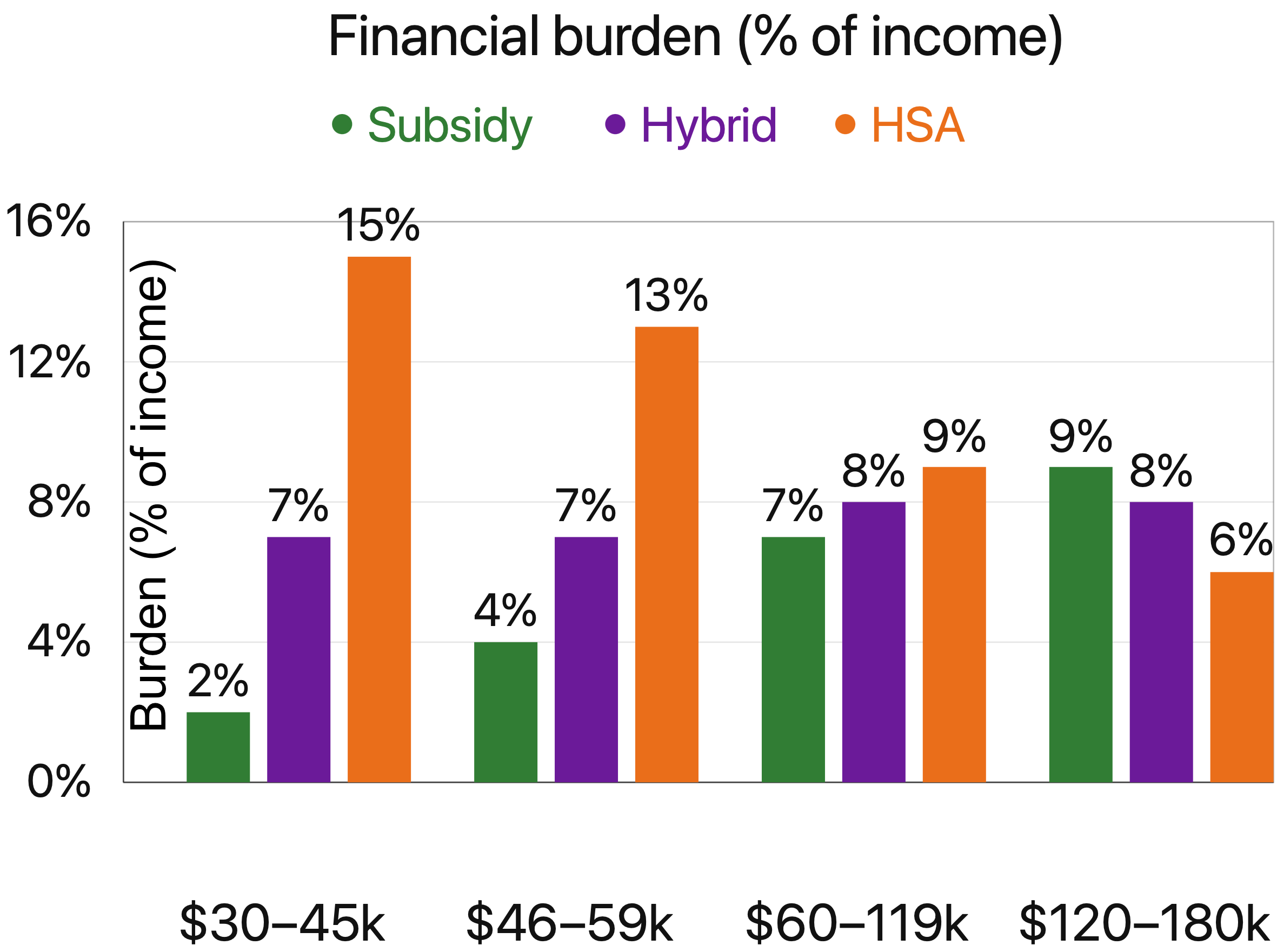

Some critics frame the subsidy debate as a proxy fight over insurer profits, arguing that extending credits primarily benefits insurance companies rather than households. Insurers have reported solid profits in recent years, but those results reflect a mix of factors, including enrollment growth, risk adjustment transfers, and pricing discipline across different markets. Marketplace plans operate under regulated margins and medical-loss rules, and profitability varies widely by state and insurer. As a result, profit figures alone do not resolve the core policy question of who bears costs when subsidies expire: households facing higher premiums, households facing higher deductibles, or taxpayers financing continued support.Why it matters: The practical question is not whether the debate “wins” for left or right, but who pays—premiums, deductibles, or both—across income levels and coverage pathways. When coverage arguments collapse into slogans, households can be left with less clarity about their real financial exposure and fewer workable options that blend premium relief with cost-sharing protection. The following graph compares likely finacial impact of Subsidy-based, Hybrid, and HSA models. The hybrid illustration is not a proposed healthcare plan, but a representation of how competing priorities — affordability, risk sharing, and individual responsibility — might be balanced under compromise. Similar tradeoffs appear across many areas of the economy, but healthcare magnifies them because costs are unpredictable and outcomes are morally charged.

Financial burden (% of income): Subsidy, Hybrid, HSA. Subsidy reflects premium contribution caps; Hybrid and HSA are modeled examples. Most relevant for non-employer coverage (e.g., self-employed, gig work, early retirees, between jobs).

Claim: “Most marketplace enrollees will face unaffordable premium increases across the board” if the enhanced ACA credits expire.

Origin: Headline-driven messaging and commentary that generalizes the cliff to nearly all enrollees.

Verdict: ⚠️ Misleading

Rationale: The direction of change is well established—many who currently receive enhanced assistance would pay more if credits lapse—but impacts vary by income, plan choice, and local pricing. “Across the board” framing overstates uniformity and obscures that some households will be less affected than others.

Claim: “The cliff is exaggerated because most people above ~$45–60k already have employer coverage, so they won’t be affected.”

Origin: Commentary minimizing the cliff by treating employer coverage as near-universal above a threshold.

Verdict: ⚠️ Misleading

Rationale: Many middle-income households do have employer-sponsored insurance, but marketplace enrollment includes self-employed workers and those without affordable employer options at many income levels. The claim converts a common pattern into a blanket rule that does not hold universally.

Claim: Redirecting subsidy dollars into HSAs would lower total household healthcare burden for most people compared with extending the enhanced credits.

Origin: Advocacy arguments for HSA-centered alternatives to premium subsidies.

Verdict: ❓ Unsupported

Rationale: Whether HSAs reduce overall burden depends on how much funding is provided, plan design, deductibles, expected utilization, and whether people can reliably cover large out-of-pocket exposure. The claim is frequently asserted in broad terms without a single agreed, publicly established model in the cited coverage.

Claim: Democrats want to keep the subsidy structure primarily to protect insurer profits.

Origin: Cynical framing in partisan commentary linking subsidy extension to insurer motives.

Verdict: ❓ Unsupported

Rationale: Insurer profitability can be debated with data, but the claim as stated asserts a primary motive without direct evidence in the coverage cited here. Reporting more commonly attributes the push to coverage retention, affordability, and political incentives rather than a documented profit-protection intent.

Claim: If enhanced credits expire, it proves the ACA is illegal and will be struck down by courts.

Origin: Viral legal commentary conflating a policy deadline with the ACA’s constitutional status.

Verdict: ❌ False

Rationale: The subsidy expiration reflects statutory design and congressional action or inaction; it does not determine constitutional validity. Treating the cliff as legal proof is a category error.

Rationale: The documented basis for the cliff is statutory timing plus unresolved partisan disagreement over extension terms. The cited coverage does not provide corroborated evidence of coordinated planning between lawmakers and insurers to engineer disenrollment. Source: AP

Rationale: Disputing assumptions is not evidence of fabrication. The claim offers no verified proof that estimates were invented, and mainstream reporting treats them as projections tied to policy formulas and observable pricing inputs. Source: Reuters

Rationale: No credible reporting or official documentation supports such a directive. Coverage of the cliff centers on legislation and subsidy mechanics, not punitive administrative cancellation policies. Source: CNN

| Outlet | Bar | Score |

|---|

| Outlet | Spin | Factual integrity | Strategic silence | Media distortion |

|---|